The first time you arrive in Manchester, it can feel a bit like standing at a party where everyone else is already halfway through a very enthusiastic conversation. The city doesn’t announce itself with ceremony or pageantry. It just is. And that is exactly what makes it so brilliant.

Manchester is the original modern city. Not in the fashionable sense but in the actual historical one. It was here that steam first powered cotton mills on a city-wide scale. Where the world’s first railway station appeared. Where Rolls met Royce. Where graphene was discovered. Where suffragettes launched their first rally. And where Joy Division and The Smiths and Oasis all took turns redefining what it meant to sound like northern England.

The skyline is a curious mix of soot-dark warehouses, shimmering glass towers and buildings that look like they were designed during lunch breaks and never properly reconsidered. But if you look a little closer, the story of a city that has spent over two hundred years reinventing itself becomes unexpectedly clear.

A Roman fort, a wool town and the start of something big

Manchester begins, like so many British cities, with the Romans. They called it Mamucium, which sounds like a mild skin complaint but actually means ‘breast-shaped hill’. The fort was built around 79 AD, the site of it is now part of Castlefield Urban Heritage Park, surrounded by office blocks and a museum or two. After the Romans packed up and left, Manchester drifted into quiet obscurity, turning itself into a modest market town and then a somewhat more industrious one.

By the 17th century, it was known for wool and weaving. But it was the 18th century that properly lit the fuse. Cotton arrived from the colonies, water power was replaced by steam, and Manchester became the workshop of the world. Within a few decades, it was producing half of all the cotton goods sold across the globe. Workers poured in. Mills sprang up faster than anyone could count. It was noisy and crowded and filthy and astonishing. There were chimneys everywhere and smoke that turned your clothes grey by lunchtime.

Friedrich Engels lived here for a while and wrote about it with equal parts horror and fascination. Charles Dickens visited and did much the same. But they both recognised the same thing. Manchester was not just an industrial city. It was an idea. An experiment in what happens when money, machines and masses of people are thrown together with very little planning and even less concern for comfort.

The birth of a radical city

If there is one thing that defines Manchester more than its industry, it is its appetite for a good argument. This is a city that has always been a bit allergic to being told what to do. It was here, in 1819, that tens of thousands gathered in St Peter’s Field to demand parliamentary reform and were met with sabres and soldiers. The Peterloo Massacre, as it came to be known, is still one of the grimmest and most galvanising moments in British protest history.

Later, the Chartists held their rallies here. The Co-operative movement was founded just down the road in Rochdale. The suffragettes emerged from the terraced streets of Manchester’s industrial suburbs. And at the Free Trade Hall, Bob Dylan went electric and a man in the balcony shouted ‘Judas’ with such venom it has become part of music legend.

The city’s radical spirit never really went away. It just took new forms. Punk found a home here. So did rave culture.

A city that keeps rebuilding

Manchester has had more than its fair share of disasters. A deadly flood in the 19th century. A devastating IRA bomb in 1996. But in each case, the city took the opportunity to rebuild, often with startling ambition. After the bomb, the city centre was redesigned almost completely. Out went the tired shopping arcades and in came bright plazas, steel-and-glass malls, and a giant wheel that turned slowly in front of the cathedral until it was eventually packed up and moved to York.

The modern city is still proud of its past but it no longer lives in it. The canals are no longer choked with coal dust but lined with cafes and yoga studios. Old warehouses have been converted into lofts and theatres and bookshops. Ancoats, once one of the grimmest slums in Britain, is now home to pasta bars, vinyl stores and an award-winning bakery that sells out of sourdough by 10am.

Yet somehow it all still feels honest. Manchester doesn’t pretend it was always pretty. It just makes a strong case for being interesting.

What to do in Manchester today

If you’re visiting, you’ll find Manchester an unusually walkable place for a city of its size. The Northern Quarter is a good place to start. It’s full of coffee shops where no one orders anything larger than a medium and every chair looks like it was found on a pavement somewhere in Sheffield. There are record stores, comic shops, tattoo studios and about six different places selling handmade ceramics. You’ll find murals, music, good falafel and, occasionally, a man with a ferret on a lead.

From there, you can wander towards the Science and Industry Museum, built on the site of the world’s first passenger railway station. It’s an excellent place for anyone who enjoys engines, looms and the occasional explosion of steam. The nearby John Rylands Library is a gothic masterpiece where the reading room looks like it should be full of wizards.

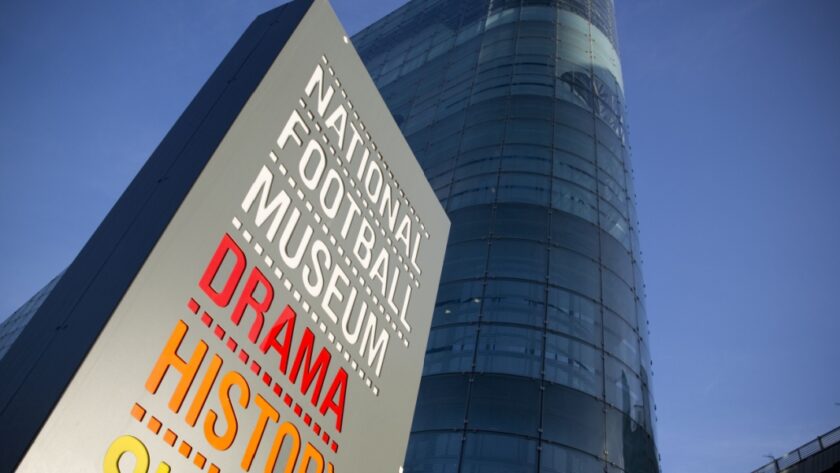

Art lovers can duck into Manchester Art Gallery, which is rather better than it needs to be, and includes everything from Pre-Raphaelites to contemporary video pieces. Football fans have two cathedrals to worship at. Manchester United at Old Trafford and Manchester City at the Etihad. Both have museums, shops, and more than enough opinions.

The People’s History Museum is also worth a visit. It tells the story of democracy in Britain through banners, leaflets, and objects that make you realise just how hard-won the right to vote really was. It’s quietly moving and doesn’t feel like homework.

Food, drink and Mancunian pleasures

Manchester does food well. It used to be all pie and chips and Sunday roasts but the past twenty years have seen an explosion of ambition and variety. The city now boasts Michelin stars, excellent Indian kitchens, street food markets, Caribbean takeaways, and Vietnamese cafes squeezed into railway arches. The Curry Mile in Rusholme is legendary, though it’s more of a curry four-hundred-metres these days. Chinatown, just behind the town hall, is one of the largest in Europe and reliably good.

Pubs are a serious business here. The Peveril of the Peak is a little green-tiled treasure with a loyal local crowd. The Briton’s Protection has been serving since before the Battle of Waterloo and stocks an intimidating number of whiskies. You’ll find craft breweries, dive bars, jazz nights, and rooftop terraces with strong views and stronger cocktails.

Final thoughts

Manchester is not a city that tries to seduce you with charm. It is not neat. It is not quaint. It is not a postcard. But it is endlessly surprising. You come for the history and stay for the energy. You get talking to a stranger at the bar and they turn out to be launching a radio station. You stumble into a basement venue and leave with a new favourite band. You go to see the museum and end up at a poetry reading in a converted mill.

In short, Manchester is the kind of place that gets under your skin without ever really asking your permission. And long after you leave, you may find you’re still thinking about it.